Growth Strategy Matrix

A Builder’s Guide to Positioning Your Product

Hey, I’m Marco 👋

I build in public toward €1M, and you get to watch and steal everything I learn. You can read more about me and my project here.

Revenue to date: €220,049 / €1,000,000

Every product lives in a market… even when its founder pretends it doesn’t.

And the market, at its core, only asks two questions:

Are you better?

Are you cheaper?

Everything else is noise.

Everything else is storytelling.

For solopreneurs like us, this is even more true. We often build fast, ship faster, and hope that traction will magically follow. But no matter how much we hustle, how many nights we spend tweaking the UI, or how many features we stack on top of each other, one thing is certain:

If you don’t know where your product sits on the map, you’re building blind.

That’s why I want to revisit one of the simplest, yet most powerful, frameworks for understanding how products grow: the Growth Strategy Matrix, created by Tony Ulwick.

This matrix helps you answer a fundamental question:

Given the job your customers are trying to get done, and the cost they’re currently paying to get it done, which strategy gives your product the highest chance of success?

Before we dive in, a quick note.

A while ago I wrote an article about Jobs To Be Done, the idea that people don’t buy products, they “hire” products to help them make progress. If you want a refresher, you can read it here → Observe.

For now, let’s jump straight into the matrix.

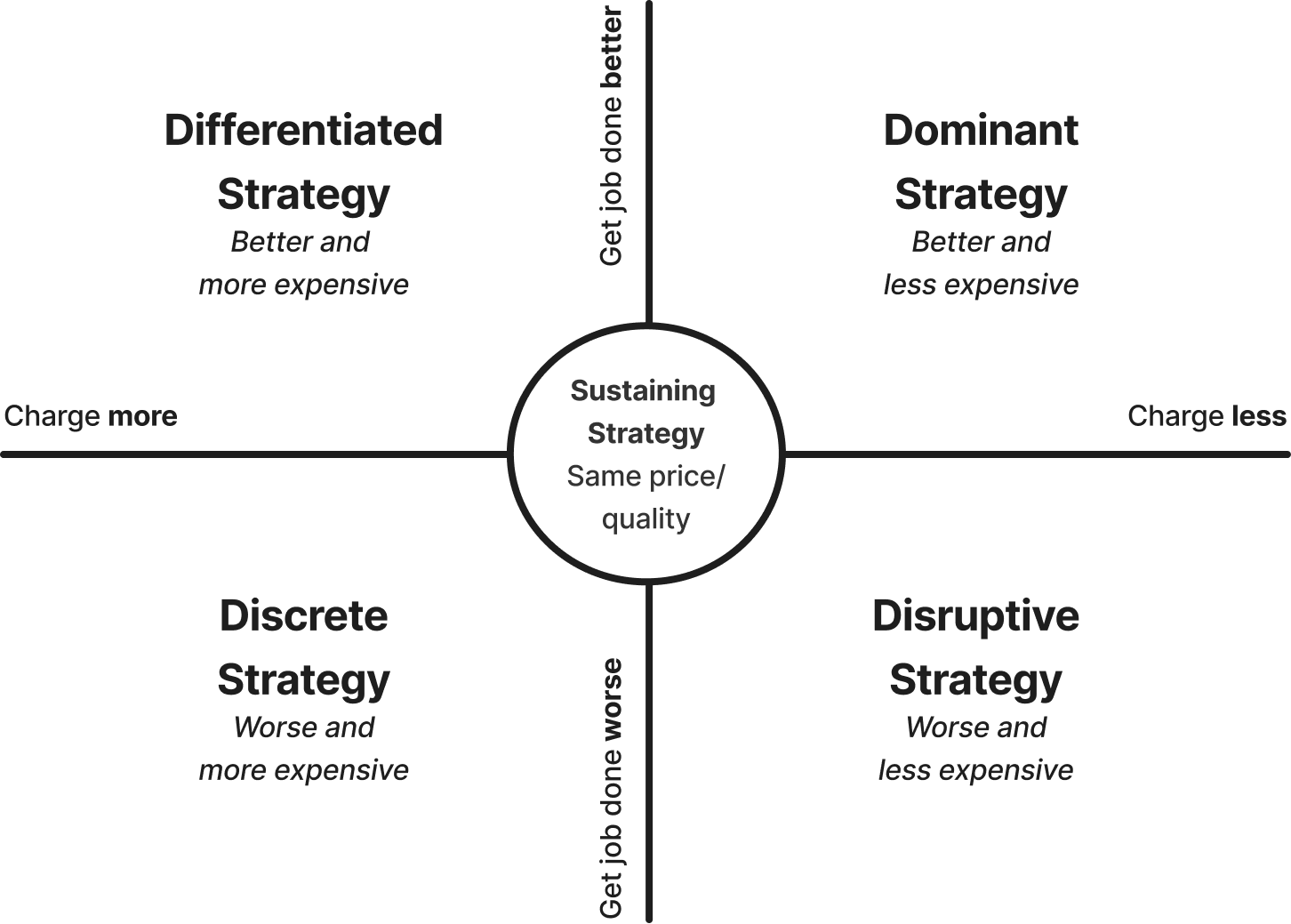

What the Growth Strategy Matrix Really Shows

The Growth Strategy Matrix is built on two variables:

How well a product helps customers complete their Job To Be Done (better or worse).

How much it costs compared to current solutions (more expensive or cheaper).

From these, four quadrants (plus a “limbo”) emerge:

Better & More Expensive

Better & Cheaper

Worse & Cheaper

Worse & More Expensive

Same price / same quality (the limbo zone)

Each of these leads to a specific strategy.

Here’s the visual layout:

The Differentiated Strategy

Better & More Expensive

This strategy targets customers who are underserved: people who are currently using a solution that doesn’t fully meet their needs. They want something better, and they’re willing to pay more.

Typical pattern:

Enter a market dominated by established companies

Deliver something dramatically superior

Charge a premium

Capture profit rather than market share

Think of:

Nespresso: premium coffee experience

Nest: a thermostat seven times more expensive than the market average

Dyson: vacuum cleaners priced like luxury goods

Tesla: early Roadster days, ultra-premium EV

Nest is one of the clearest examples.

They entered a boring, saturated market… and blew it open by making a thermostat intelligent, beautiful, and desirable. Their product was €250 when the market averaged €35, but they owned around 25% of profits with less than 10% of the market.

Differentiation is profitable, but it’s hard.

You must:

deliver true, perceived superiority

find a niche that deeply cares

justify a high price

👉 For solopreneurs?

This quadrant is possible, but demanding. It works if:

- you’re serving a high-value niche

- your users have urgent unmet needs

- you can deliver 10x performance through design or tech

But in most cases, solo builders don’t start here.The Dominant Strategy

Better & Cheaper

This is the holy grail.

You outperform the competition and cost less. When this happens, the old guard usually can’t defend itself.

Netflix vs Blockbuster

Uber vs taxis

Google Search vs everything before it

Shopify vs custom-built ecommerce platforms

Netflix is the perfect example. Before streaming:

you rented DVDs,

paid per movie,

or subscribed to expensive cable bundles.

Then suddenly: unlimited content → €7.99/month and way more convenience.

Data suggests that to win with a dominant strategy, a product must:

improve customer outcomes by at least 20%

reduce price by at least 20%

This is brutal for established companies: they can’t drop prices without destroying their margins.

👉 For solopreneurs?

This strategy is appealing… but also the hardest. Competing as “better & cheaper” usually requires:

- serious automation

- economies of scale

- strong brand trust

- or infrastructure-level innovation

Still, it’s the dream quadrant. When companies get here, they win markets.The Disruptive Strategy

Worse & Cheaper

This strategy targets:

overserved customers: people using overkill solutions

nonconsumers: people priced out of the market completely

This is where many startups originate.

You build something that helps people do the job, even if it’s not as powerful — because they don’t need all the power.

Examples:

Canva vs Photoshop

Google Docs vs Microsoft Word

Duolingo vs expensive language schools

Coursera vs universities

Fiscozen (Italy) vs traditional accountants

If you compare Canva to Photoshop, Canva loses. Badly. But Canva wasn’t trying to win that fight.

It targeted:

people who needed simple graphics

people who found Photoshop overwhelming

people who couldn’t afford Adobe’s pricing

And it grew into a giant.

There’s also a process here:

Start at the bottom → serve simple use cases → improve over time → eventually threaten the established companies.

This is Clayton Christensen’s classic “disruption curve”.

👉 For solopreneurs?

This is the most accessible quadrant.You don’t need to beat the market — you need to serve people who are currently ignored.

This is where most indie hackers win.The Discrete Strategy

Worse & More Expensive

This sounds insane, but it happens whenever the customer is trapped, when alternatives are limited or unavailable.

Examples:

Motorway service station (in Italy are called Autogrill)

Airport shops

Stadium bars

ATMs in remote areas

You pay €4 for a bottle of water not because it’s good, but because you have no choice.

This is not where you want to build your product… unless you’re in a genuinely constrained market (rare for SaaS).

👉 For solopreneurs?

Avoid this entirely. Your users always have alternatives. Always.The Sustaining Strategy

Slightly better or slightly cheaper

This is the middle zone, the limbo.

Your product is similar to existing solutions, maybe 5% better or cheaper.

This strategy:

works for established companies

kills new entrants

Why? Because customers rarely switch for tiny improvements. Changing tools costs more, emotionally and practically, than the 5% gain you’re offering.

👉 For solopreneurs?

If you’re launching something new: Avoid sustaining improvements. No one will care.

If you’re an established player, it helps you maintain position… but it’s not a growth engine.How to Actually Use the Matrix

You can’t choose a strategy without understanding your customers’ JTBD and whether they’re:

underserved → want much better, willing to pay

overserved → want simpler and cheaper

nonconsumers → can’t afford the current solution

stuck → can’t switch easily

satisfied → don’t want change

Some examples:

If customers are overserved, a Differentiated Strategy will fail: you’ll build something more complex and expensive for people who actually want the opposite.

If customers are underserved, a Disruptive Strategy will fail: no one wants “worse and cheaper” when they are begging for “better”.

Everything depends on what progress they want to make.

Putting the Strategies Into Motion

Differentiated Strategy: When to Use It

Works when:

customers are extremely underserved

you can deliver a truly superior solution

you can justify a premium price

Apple used it with the first iPhone. The industry laughed (“$500 for a phone???” - Steve Ballmer)… but the device was radically better.

Once Apple scaled, they moved toward the dominant quadrant with products like the iPhone SE.

Differentiation → then expansion.

Disruptive Strategy: When to Use It

Perfect when:

the market is over-engineered

customers are overwhelmed

pricing excludes many people

The disruption process:

Enter with something simple, inferior, cheap

Serve ignored users

Improve the product

Move upward

Replace established companies

Most solopreneurs thrive here. It’s the most realistic path from zero.

Dominant Strategy: When to Use It

Hardest to pull off.

To win:

+20% performance

–20% price

exceptional distribution

Startups dream of this. Big players fear it. But it’s rarely the first move for a solo builder.

Discrete Strategy: When to Use It

Use only when:

the context literally blocks alternatives

switching is impossible

urgency is extreme

In software, this is nearly never the case.

Sustaining Strategy: When to Use It

Works for:

established companies defending market share

products already adopted

brands with loyal customer bases

If you’re launching a new SaaS:

Don’t build a sustaining product. No one needs a 5% improvement from a stranger.

So… Which Strategy Should Solopreneurs Choose?

Let’s end with two builders you know well: Marc Lou and Pieter Levels.

Their stories demonstrate how solopreneurs naturally fit into specific quadrants.

Marc Lou

Marc Lou is a great example of how solopreneurs naturally start in the disruptive quadrant, not by outbuilding big competitors, but by serving ignored segments with simple, fast, and emotionally resonant products.

Between 2022 and 2025, Marc built dozens of products. Many failed, but each one taught him something and helped him identify overserved or overpriced markets.

Some of his early experiments included:

Mood2Movie – viral movie recommendations based on mood

Habits Garden – a gamified habit tracker (~$500/month)

Books Calculator – a simple reading progress tool that went viral

Decision Game – a small web game to help people stop overthinking

None of these were “better than the established companies”. They were simpler, cheaper, and good enough — classic disruptive strategy.

His breakthroughs came when he doubled down on this approach:

ShipFast – a fully packaged starter kit for developers, born from his own repeated pain building infrastructure

CodeFast – an AI-powered coding course for founders who want to build SaaS in 14 days

DataFast – a real-time traffic globe that turned analytics into a game

TrustMRR, IndiePage, BioAge, ZenVoice, and more — all small but highly focused tools

Marc didn’t create the “best” design platform or the “best” analytics tool.

He created tools for people who felt the alternatives were:

too complex

too expensive

or simply not built for them

This is disruption in its purest indie-hacker form.

Pieter Levels

Pieter is the king of starting simple.

Nomad List began as a spreadsheet.

RemoteOK was a job board with a basic UI.

Levels doesn’t try to be better than giants. He tries to be faster, simpler, and accessible.

Again: Disruptive Strategy.

His playbook:

identify an underserved or ignored niche

build a focused product fast

price transparently

improve based on usage

compound over years

He never tries to win the “dominant” quadrant from day one. He enters through the side door.

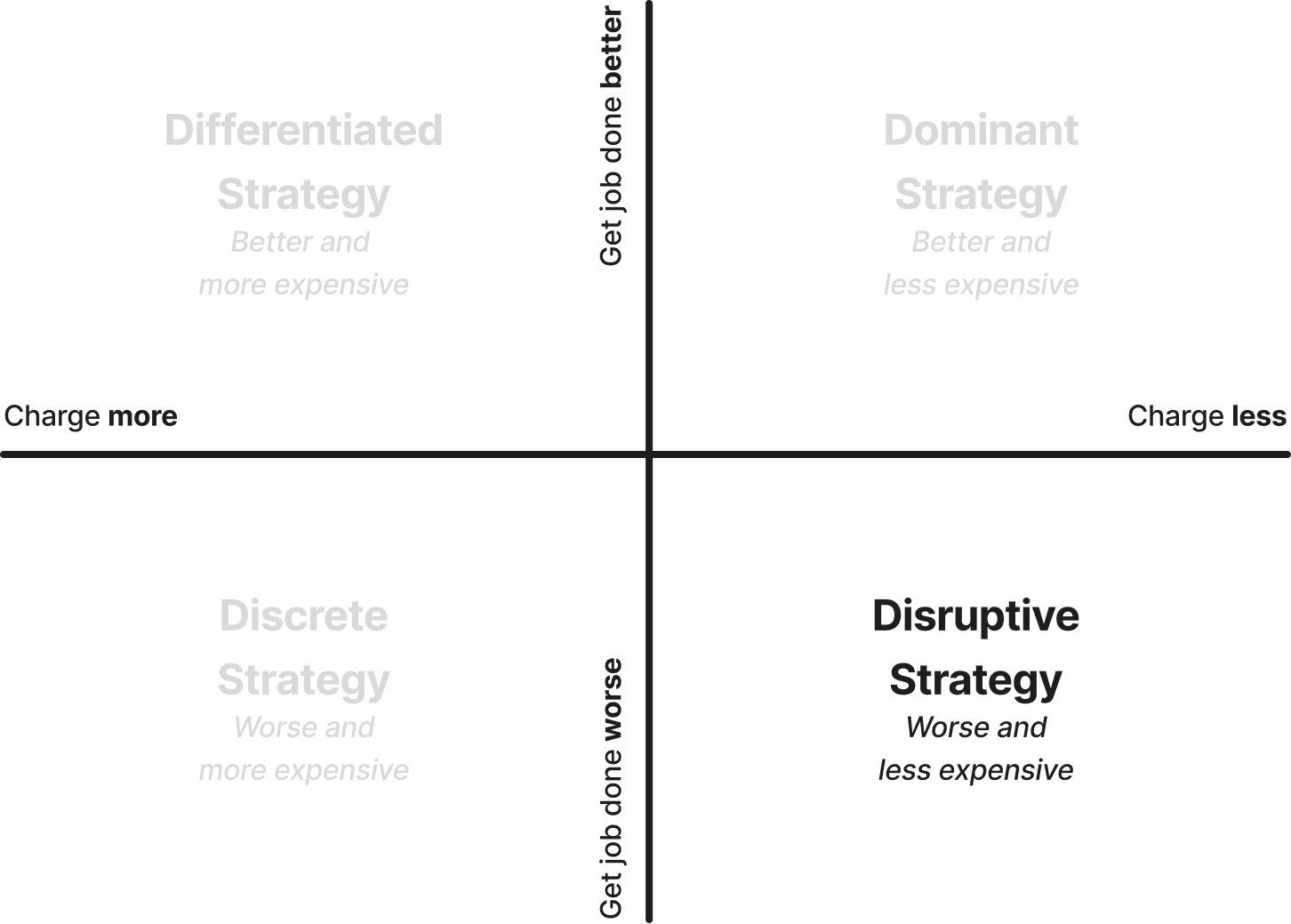

The Solopreneur’s Takeaway

Most solo builders won’t start with:

Differentiated (too expensive and complex)

Dominant (too demanding in cost + performance)

Discrete (almost never applicable)

Sustaining (not attractive enough)

The realistic quadrant (the one where your unfair advantage is speed, simplicity, and focus) is:

The Disruptive Strategy

Serve people who don’t need everything.

Serve people who can’t afford the alternatives.

Serve people who are ignored.

Build fast.

Start simple.

Grow upward.

That’s the solopreneur path.

Complimenti Mark !

Utilizzerò il tuo articolo nel prossimo thread che scriverò per X

grazie sei sempre d’ispirazione !

Bell’articolo: lo userò per le lezioni all’università 😁